A Reasonable Doubt

A Reasonable Doubt The Perfect Alibi

The Perfect Alibi A Matter of Life and Death

A Matter of Life and Death Capitol Murder

Capitol Murder Supreme Justice

Supreme Justice Gone, But Not Forgotten

Gone, But Not Forgotten Violent Crimes

Violent Crimes Fugitive: A Novel

Fugitive: A Novel The Third Victim

The Third Victim Executive Privilege

Executive Privilege Lost Lake

Lost Lake Woman With a Gun_A Novel

Woman With a Gun_A Novel The Undertaker's Widow

The Undertaker's Widow Fugitive

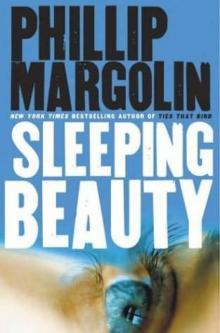

Fugitive Sleeping Beauty

Sleeping Beauty Woman with a Gun

Woman with a Gun The Associate

The Associate After Dark

After Dark Heartstone

Heartstone The Last Innocent Man

The Last Innocent Man Violent Crimes: An Amanda Jaffe Novel (Amanda Jaffe Series)

Violent Crimes: An Amanda Jaffe Novel (Amanda Jaffe Series) Worthy Brown's Daughter

Worthy Brown's Daughter Ties That Bind aj-2

Ties That Bind aj-2